Siege of Limoges

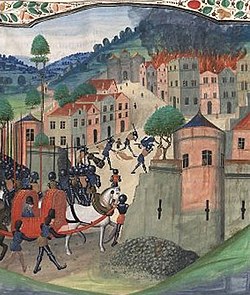

The town of Limoges had been under English control but in August 1370 it surrendered to the French, opening its gates to the Duke of Berry. The siege of Limoges was laid by the English army led by Edward the Black Prince in the second week in September. On 19 September, the town was taken by storm, followed by much destruction and the deaths of numerous civilians. The sack effectively ended the Limoges enamel industry, which had been famous across Europe, for around a century.

1. The attackers

The Anglo-Gascon force was not large but was led by three sons of Edward III; Edward, Prince of Wales; John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster; and Edmund of Langley, Earl of Cambridge. Edward was a sick man and was carried on litter. They were accompanied by experienced soldiers John Hastings, 2nd Earl of Pembroke, Sir Walter Hewitt, Guichard d'Angle and the Captal de Buch. The army was small, about 3200 strong, comprising approximately 1000 men-at-arms, 1000 archers and 1200 infantry.

1. The defenders

By the time of the siege, the Duke of Berry had left Limoges with most of his army, leaving a small garrison of 140 men. According to Jean Froissart, Jean de Cros, Bishop of Limoges, played a large role in assisting the surrender to the Duke of Berry. Sir John Villemur, Hugh de la Roche and Roger Beaufont are described in terms of putting up a last stand against the English in a town square and were captured when the town fell.

1. Sack and massacre

Froissart alleges that Edward was put into a "violent passion" in which he declared that regaining Limoges and punishing the French for its capture would be his singular goal. When the city wall fell, Froissart mentions the massacre of three thousand inhabitants—men, women and children—breaching the rules of chivalry and Edward still "inflamed with passion and revenge". Three captured French knights appealed to John of Gaunt and the Earl of Cambridge for being treated "according to the law of arms" and turned prisoners. Froissart's account is sometimes challenged as French bias. Froissart had worked for the English court, being in the service of Philippa of Hainault, queen consort of Edward III of England, but at the time he wrote he was employed by Guy de Châtillon, Count of Blois. Jim Bradbury does not dispute Froissart's account but simply states that Limoges was "not an exceptional atrocity". Richard Barber, in his biography of the Black Prince, notes that a contemporary source from Limoges only records 300 civilian casualties and other period sources don't mention civilian deaths at all, concentrating on property damage. Jonathan Sumption also records that casualties may have been 300 civilians, "perhaps a sixth of the normal population", plus 60 members of the garrison. A recently discovered and previously unread letter from Edward, the Black Prince to Gaston III, Count of Foix has cast further doubt on Froissart's claims. The letter states that 200 prisoners were taken but mentions no civilian deaths. Sean McGlynn, in his study of atrocity in Medieval warfare By Sword and Fire, examines the evidence for the massacre and concludes that it was notable as major urban areas were rarely devastated as completely as Limoges. He identifies a complex interplay of reasons behind Edward's actions, including a desire to punish the perceived treachery of the city, a frustration that he could not prevent his territories from falling under the control of the French, the effects of his illness and a desire to liquidate the wealth of Limoges and carry it away, because he could not defend it. Michael Jones reviews the evidence in an appendix of his biography of the Black Prince. He finds that the archaeological and documentary evidence points to widespread property destruction and that there were civilian casualties but not at the level Froissart states, quoting a range of sources giving the killed and captured among citizens and garrison between 200 and 400. He believes Froissart's account should be dismissed as a "slur".

1. Notes

1. External links

The Black Prince’s Sack of Limoges (1370)

Nearby Places View Menu

Limoges

1958 UCI Cyclo-cross World Championships

Haute-Vienne

English

English

Français

Français